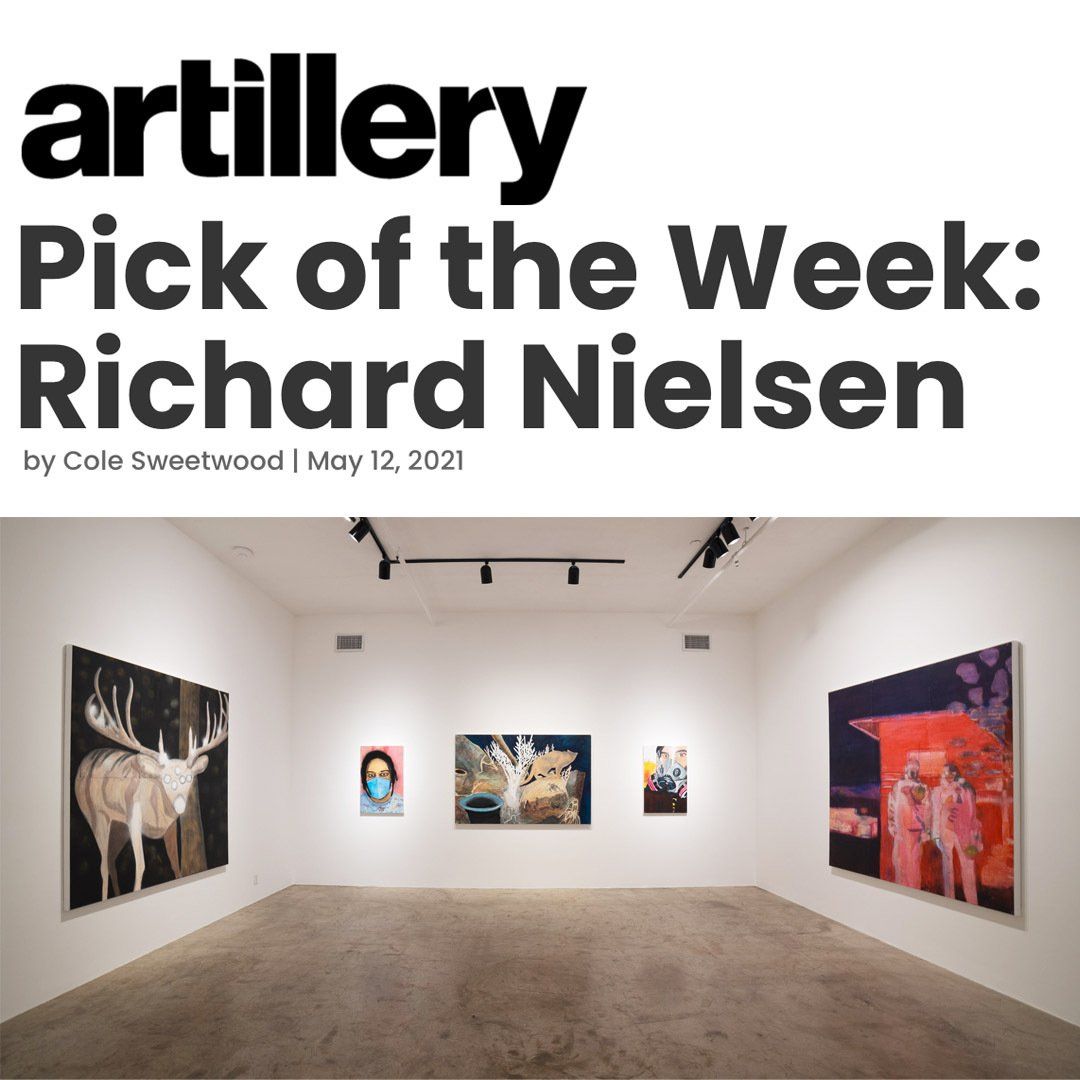

RICHARD NIELSEN

PAST IMPERFECT

April 10 - May 29, 2021

Richard Nielsen: Past Imperfect

By Denise Markonish

Senior Curator and Director of Exhibitions, MASS MoCA

“…the past is always tense and the future, perfect.”

– Zadie Smith, White Teeth, 2000

“We are the United States of Amnesia; we learn nothing because we remember nothing.”

– Gore Vidal

The grammatical principle of “past perfect” comes from the Latin

plus quam perfectum which translates to “more than perfect.” It denotes a verb used to discuss actions completed in the past. So, what occurs when we realize that this notion of “more than perfect” is, in fact, anything but? Writer Zadie Smith’s simultaneous acknowledgement of the tense nature of the past and the questioning of a more perfect future is the limbo of the 21st century. And, the most imperfectly perfect painting for this moment is Richard Nielsen’s, whose recent works at Track 16 in Los Angeles, CA, are gathered under the title

Past Imperfect. For Nielsen, the idea of past imperfection also relates to Gore Vidal’s notion of the “United States of Amnesia,” probing the question of why we forget and revealing how that very forgetting can lead to a future that is a continual feedback loop of seemingly new information.

The investigation of this process of forgetting the past and absorbing the present is evident in Nielsen’s process, which begins by him mining existing imagery – from friends, from the news media, and from Instagram feeds. There is something both familiar and alien to his paintings such as

White Tail and

Surprise Rack, both of which start from images captured by night vision cameras on a friend’s property. In the paintings, we see the eerie moments when a deer’s eyes flash alien as they are caught by nearby illumination. The animals appear otherworldly, yet they exist on earth right beside us. Nielsen then pairs these with images that evoke a startling loneliness such as

Uncle Arne and Aunt Marie and

Maternity Park.

The first begins with an extremely cropped composition of Aunt Marie sitting in the corner of a room, tissue in hand. In the opposite corner – cropped to the point where you don’t see the person – you realize that Aunt Marie is sitting by the side of a hospital bed. Nielsen’s paint drips on the floor and dark stained walls then take on an end-of-life melancholy. Whereas in

Maternity Park, the figure is front and center, but that doesn’t mean it is immediately legible. In this painting, we are confronted with a human dressed as a panda cradling an actual baby panda. If one didn’t know that this was a method used to rescue cubs in the wild, you would be hard pressed to understand why this is happening, yet the tenderness and solitude of the image is readily apparent.

Throughout

Past Imperfect, Nielsen gives his audience a glimpse into present day society, a place where experience is mediated through the images we choose to put online, images that can have great meaning in one moment and fade to obscurity then next – falling prey to the United States of Amnesia. This is nowhere more prevalent than in 2020/21, for the moment the Covid-19 pandemic hit, we were all forced to disengage with in-person humanity. It’s like that panda suit became a precursor to the face masks we would all soon be sporting.

Toto and the Doorman has a similar isolation evident in

Uncle Arne and Aunt Marie. However, in this composition, two people, disconnected from one another, patronize an art gallery. The word “open” is taped onto the door (an almost desperate plea to come inside when so much is shuttered), one patron is wearing a mask while the other has theirs around their chin, and in the background, we see a painting of Nielsen’s rainbow which often appears in his work. You might think: this is what galleries feel like. Yet the presence of those face masks alongside the distance between the two visitors reminds us of this unprecedented moment.

This painting is further reinforced through the inclusion of Nielsen’s facemask portraits. In March 2020, just as the world began to shut down as a result of Covid-19 Nielsen started gathering selfies of friends in their facemasks. The result is a series of over 60 paintings and counting that capture the surreal moment of social distancing and extreme politics across the United States. Who knew that a simple face covering would be a political statement, but that is just what they became – democratic message boards front and center on our faces. At Track 16, Nielsen exhibits eight of these paintings (another 49 are on view at MASS MoCA in North Adams, MA in the exhibition

This is Not a Gag through 2021). In these paintings, though most of the faces are obscured, Nielsen always paints his subjects’ eyes with deep emotion – a combination of fortitude and sadness at some times, while other times the eyes speak of sheer determination. The selection on view here includes portraits such as Shant Kabaday in a construction respirator; Dr. Charlotte S, Carlson, a doctor in a N95, face shield, and blue scrubs; Michelle Fierro in a mask that reads “Wuhan” in the Wu Tang Clan logo alongside “Virus” in the Vans sneaker logo; and RJ, an essential worker wearing an upside-down stars and stripes mask. RJ’s eyes are not visible behind the reflective sunglasses he wears, but you can imagine their resolve.

One of the last pieces in Nielsen’s exhibition brings us to the past, 1945 to be exact, when his great uncle was a Danish Freedom Fighter. In this painting, we see a group of five men standing on a psychedelic cobblestone street – all in black suits with white armbands and guns slung across their shoulders. Nielsen titles this work

Antifa Denmark 1945, Danish Freedom Fighters, Great Uncle. By adding the phrase “Antifa” Nielsen combats societal amnesia by reminding us that although Antifa – the left-wing anti-fascist group that became one of the many targets of right-wing vitriol slung by Donald Trump – became a common name in 2020, the group actually goes back to Europe in the early 20th Century (in particular to battle Benito Mussolini’s Italian Fascist Government in the 1930s). By placing the mask portraits alongside a painting referencing the activism in the artist’s own genealogy, Nielsen brings past and present together – reminding us that while both are imperfect, it is still worth trying for the future.

In the end, Nielsen’s work becomes like the painterly version of British documentarian Adam Curtis’s films. Curtis, like Nielsen, mines our visual history, linking past and present to understand why we forget and how. As a result of this investigation, both Nielsen and Curtis present to us alternate views of alternate realities. In a blog entry at the BBC website, Curtis writes: “Throughout the western world, new systems have risen up whose job is to constantly record and monitor the present – and then compare that to the recorded past. The aim is to discover patterns, coincidences and correlations, and from that, find ways of stopping change. Keeping things the same.” The arresting of change – the amnesia that comes with the constant barrage of image replacing images – reminds us that just as remembering and forgetting are flawed, the past is imperfect and the future doesn’t yet exist. Nielsen’s work essentializes this liminal space of the plagued present – by celebrating the now as a mash up of insurgency and activism, of social media and social distance.

INSTALLATION VIEWS

ARTIST TALK

360° WALKTHROUGH

ABOUT THE ARTIST

Richard Nielsen is an artist, painter, photographer and printmaker. With a background in lithography and etching, Nielsen's painting and photographic practice is informed by the expanded field of printmaking. Committed to offering printmaking opportunities to established and emerging artists, Nielsen's Los Angeles studio, Untitled Prints and Editions, has hosted guest artists from around the world. Nielsen has been a close collaborator with Lauren Bon and her Metabolic Studio since 2007.