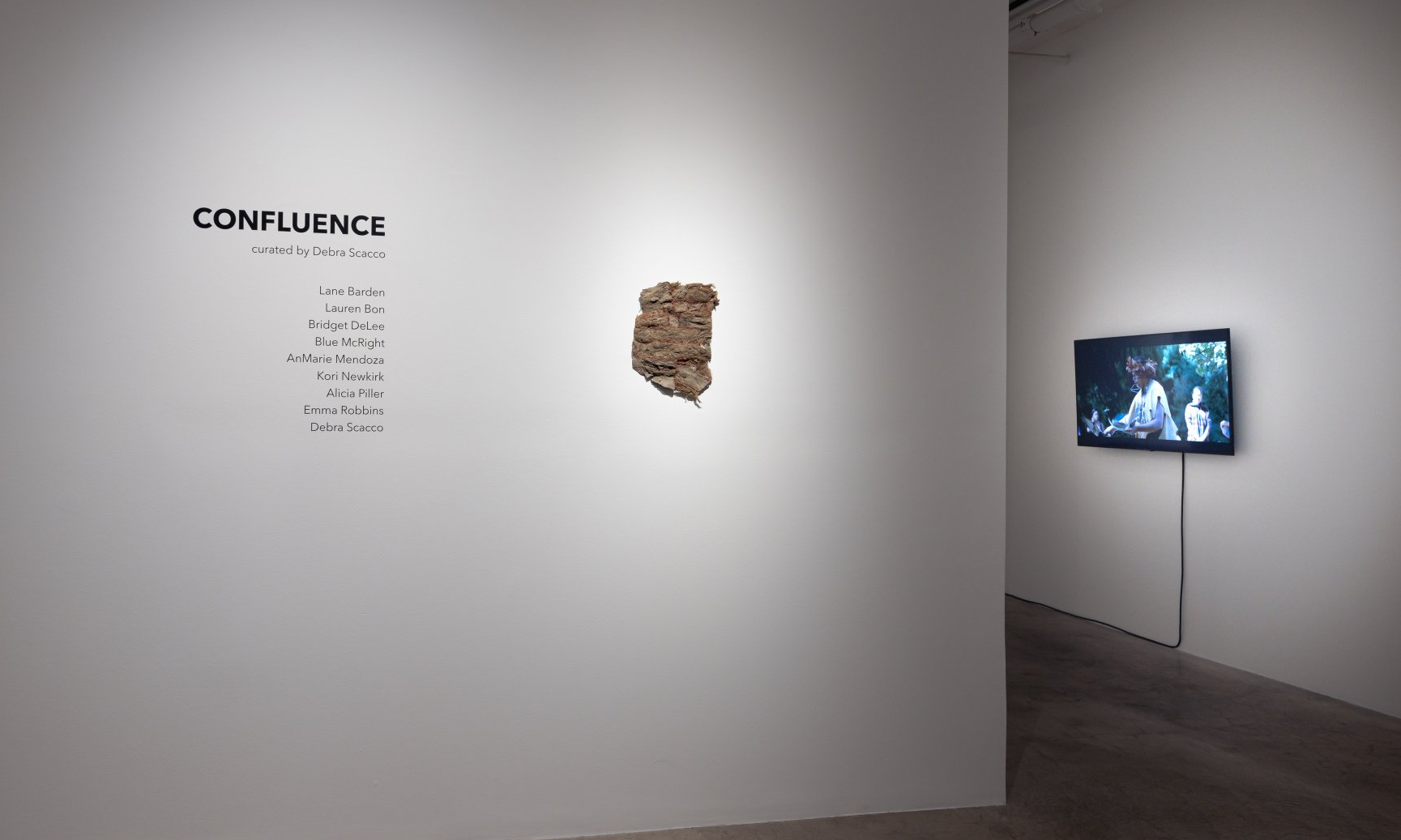

CONFLUENCE

Curated by Debra Scacco

August 6 to September 3, 2022

Exhibition Text by Michael Atkins

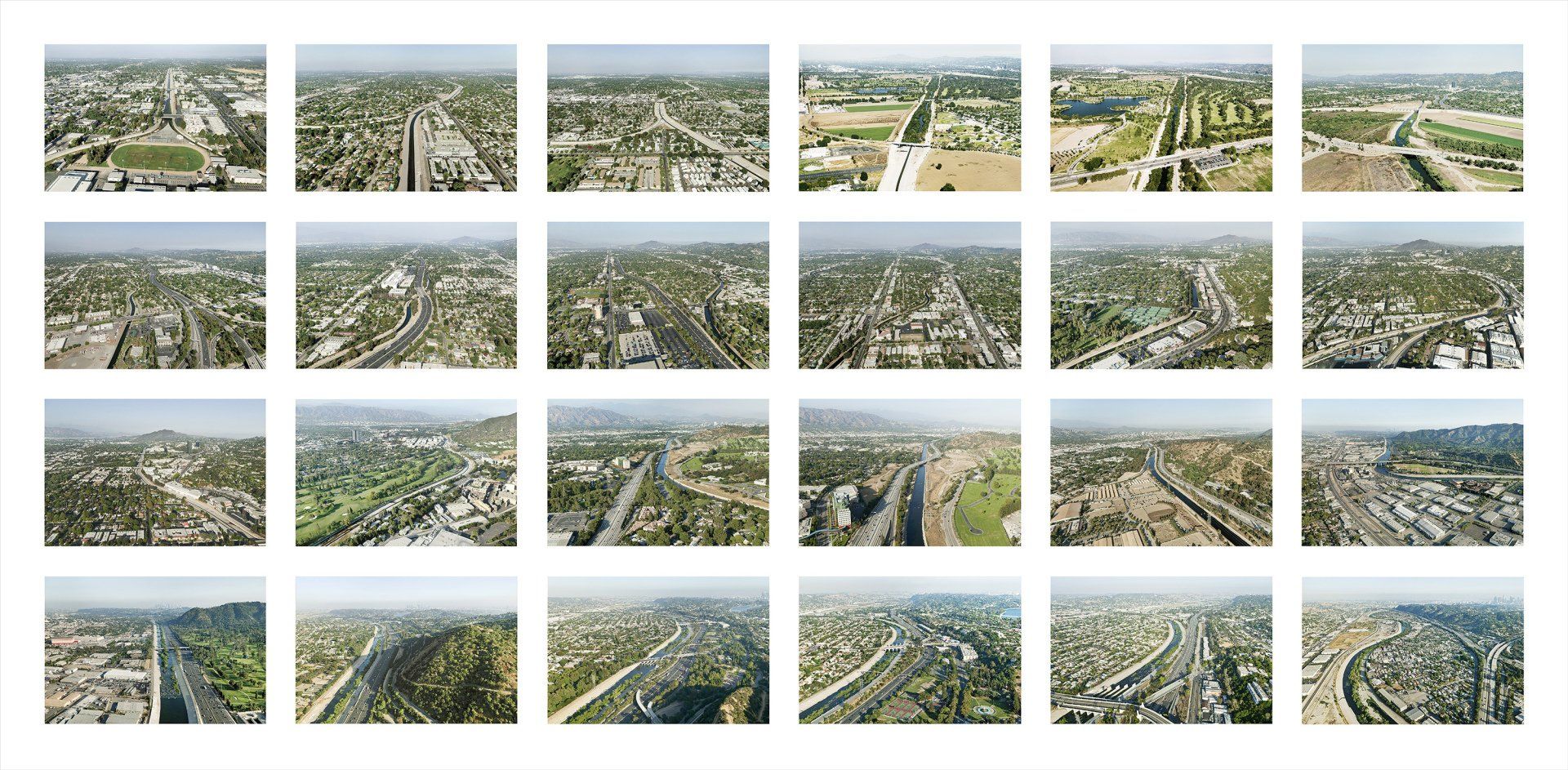

If water is life, how long can we survive a drought? When the Colorado River runs dry, how does the American West mitigate an inglorious demise? How do we balance our present built environment against the dynamics of nature? California, and the greater Southwestern United States, is grappling with a water crisis so severe it’s spawning new terminologies to articulate its severity. Despite entering the 22nd year of a megadrought caused by our concrete commitment to impermeable landscape redesign, by and large, business continues as usual. We need not look farther than downtown Los Angeles to observe a river in its afterlife, a foundation for a crisis poured long ago.

At the dawn of our present overheated century, artist-activist-historian Jenny Price called for the rearticulation of our environmental ideals, nominating the Los Angeles River as the icon of 21st century environmentalism. A quarter of a century later, a new group show, Confluence, curated by artist Debra Scacco, explores a convergence of water issues through the perspectives of nine artists across mixed media. Confluence excavates a lost future, examining the feedback loops created by encasing the city’s life-giving force in concrete and sentencing it to serve its metropolis as a storm drain.

Engineers faced a vexing problem a century ago. Under the extreme pressure of developers and civic boosters to solve the issue of devastating floods, engineers dreamt a concrete dream, and contorted the river into a fixed channel, enabling massive housing construction throughout the floodplain. For a city founded on land and water theft, the concretization of the Los Angeles River marked a point of no return for settler society in manufacturing its city of the future. In doing so, last century’s leaders sealed the fate of the city to reject and disavow itself of the Indigenous technologies and practices that emphasize balance. The Los Angeles River once provided shelter, sustenance and spiritual guidance for its people. Today, society scrambles to reassemble the past as it careens toward extinction.

As evidenced in AnMarie Mendoza’s documentary The Aqueduct Between Us, our concrete current culture was not without its opponents and resistors. The documentary tells the history of water, slavery, and development of the LA basin from a Tongva perspective, and is essential viewing for all Angelenos. The filmmaker’s juxtaposition of stark hardscapes and cacophonous street life with the serenity and stillness of California’s natural waters illustrates the inability of settler society to properly account for water as a blessing essential for life.

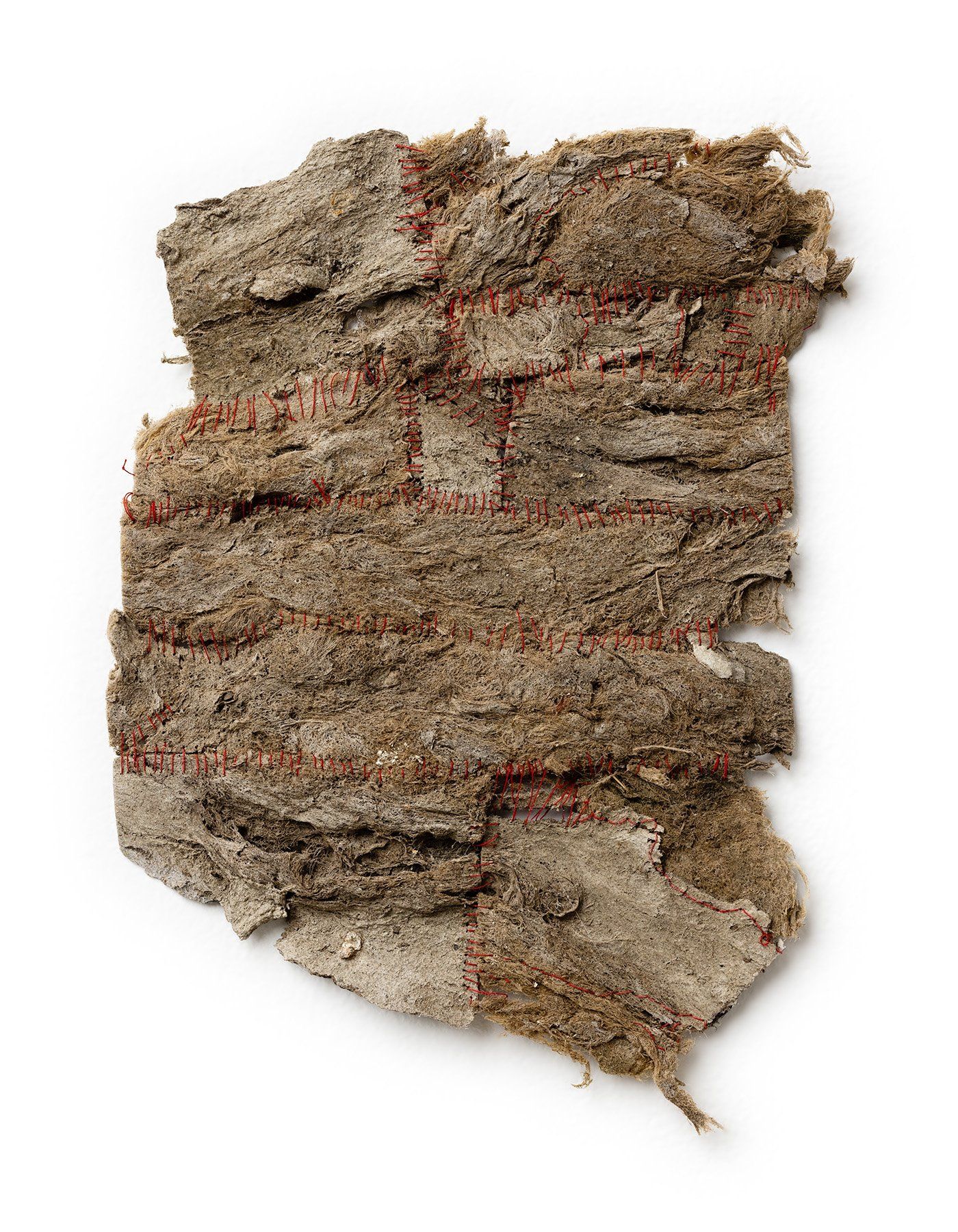

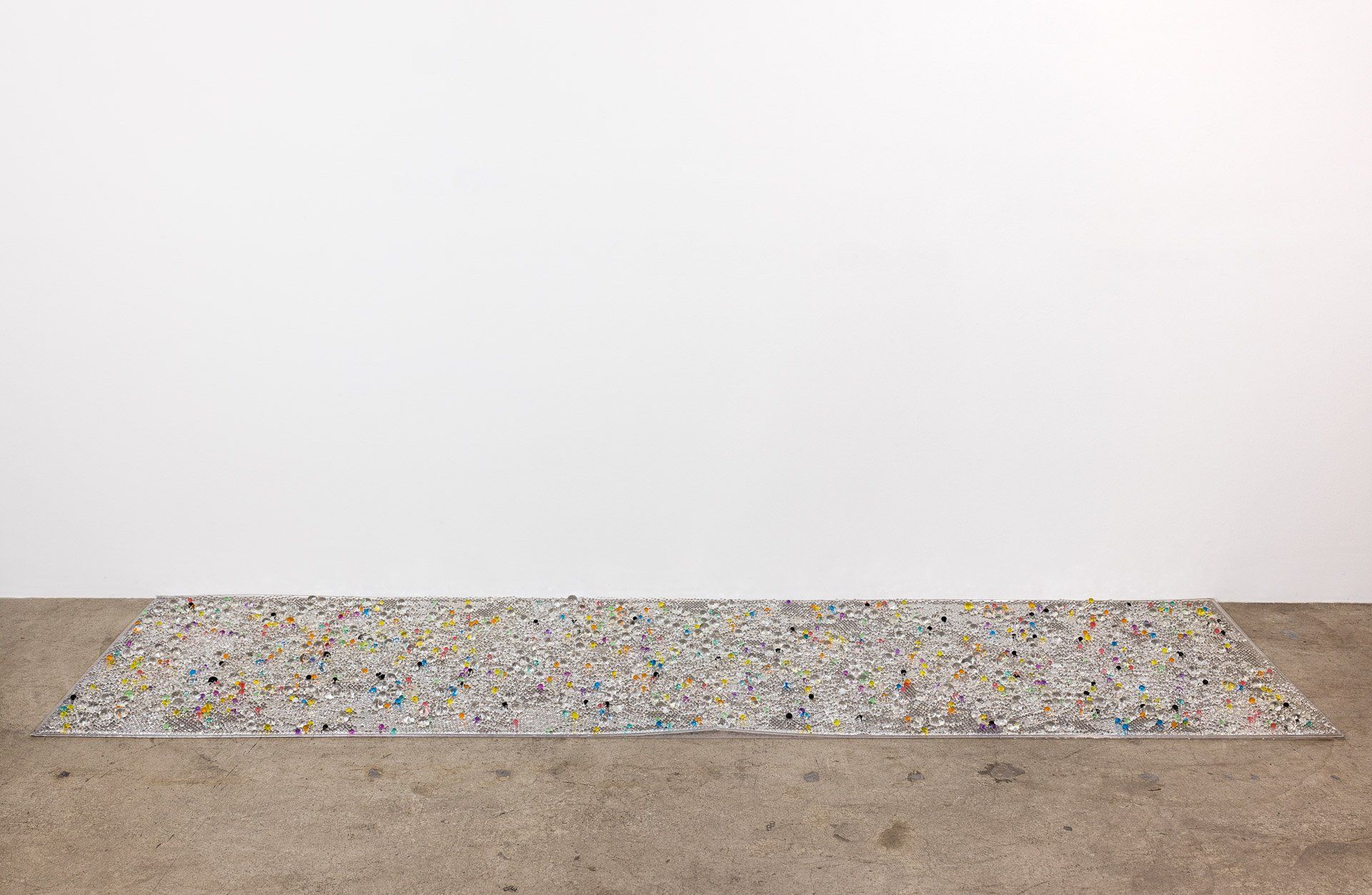

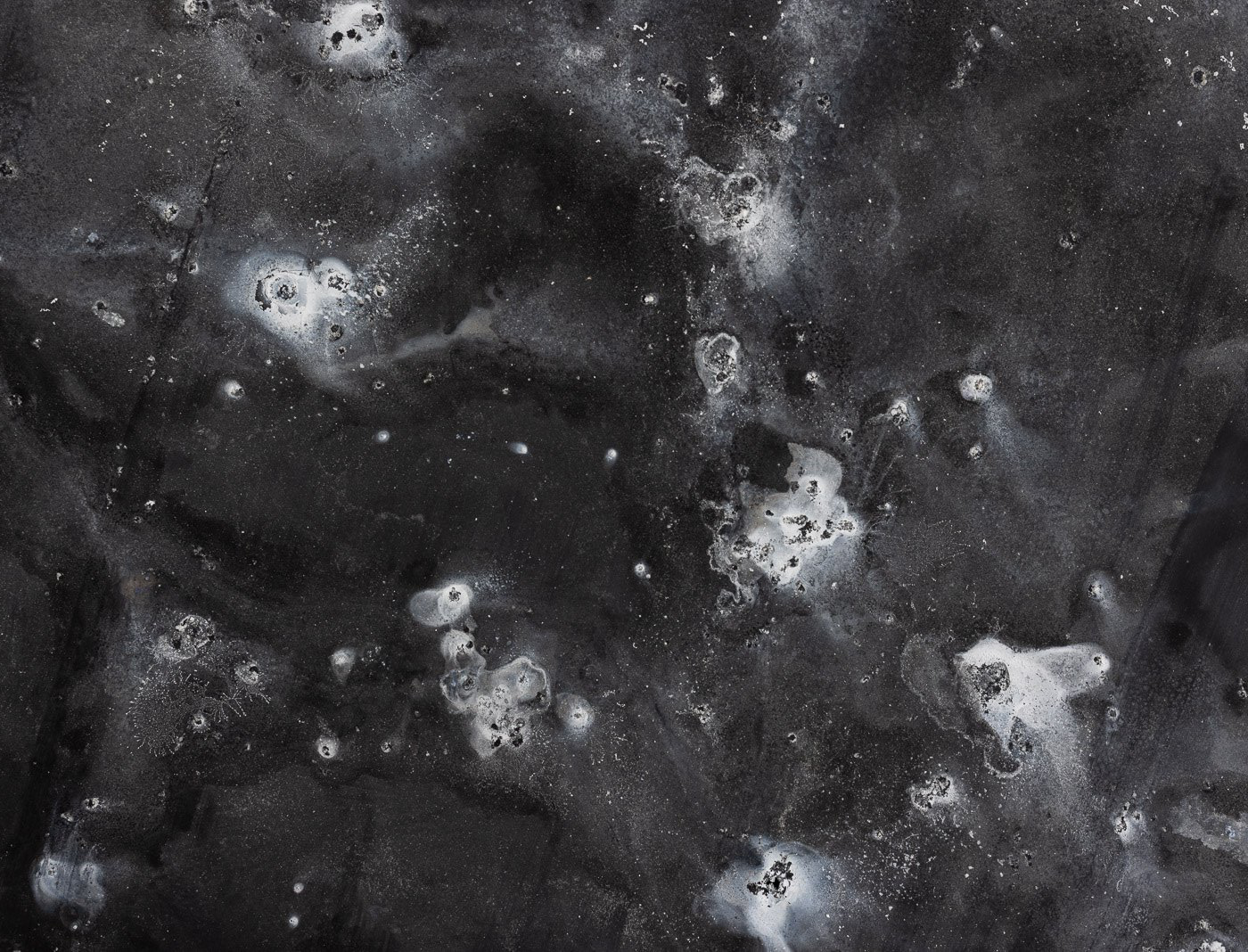

A major theme throughout the exhibition is the impermanence of objects otherwise considered permanent. By assembling artworks from materials and water itself sourced from the LA River, the artists explore a time span longer than human life, syncing instead to geological time, measuring what is left behind in the irreversible process of extraction, redirection and mismanagement. Forty years of public interest and activism has percolated to reestablish the river’s designation as a waterway, and rehabilitate the flood control channel to invoke its verdant past. Equal parts river and infrastructure, Confluence demonstrates that despite massive efforts to bury the river, it remains a resource to its people, and a source of inspiration and imagination to its artists.